My first reaction was fury. Hundreds of evacuees were lined up on the blazing hot concrete waiting to go through metal detectors. Many had been picked up from the Superdome and off freeways, and most had been stranded without food and water. I could not believe I was in the United States. I was stunned by how ill prepared our government was for a disaster of this kind, and how completely inadequate the help was for the evacuees.

I began talking to a few people who had checked into the shelter and were gathered under awnings, but it took me a while to make my first photograph. I was in partly in shock, and just listened and tried to comfort the people around me. The sadness was overwhelming, and the pain heart wrenching. It took me a few days to begin to work.

And from there I documented the aftermath of Katrina for over a year.

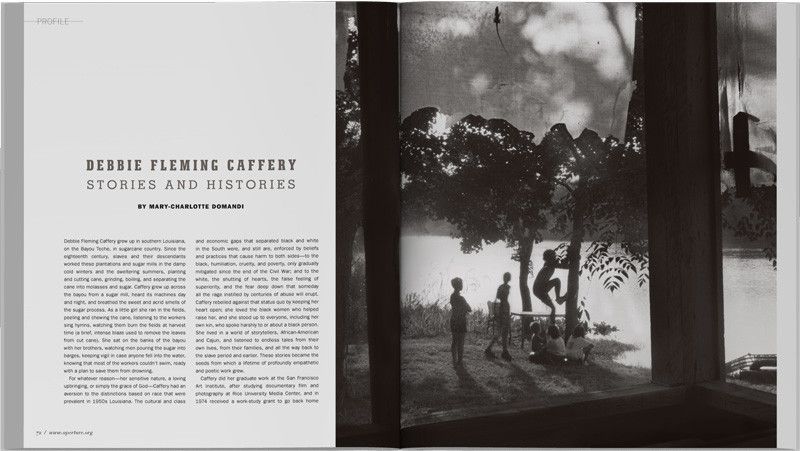

Debbie Fleming Caffery: A stormy day in the Ninth Ward in August, 2006.

The government’s lack of concern and ability to care for the poor during and after Katrina was a crime. And it didn’t help matters when both politicians and preachers alike insinuated that, “these people deserved the destruction.” One bright spot were the volunteers who showed up from the Louisiana countryside and across the U.S., providing food, clothes, and money, and, as time went on, helped to rebuild the homes of many evacuees.

Despite my initial hesitancy to photograph at the River Center Shelter, I learned over and over again that most people wanted their stories told. I’ll never forget how surprised and grateful people were when I brought them a copy of the magazine filled with their portraits.

I discovered later that the images I took the year after Katrina became extremely important to some residents in the years that followed. They had lost everything and had no way to photograph their homes, neighborhoods and churches. It was a powerful reminder of how important it is to give back to the people we photograph. We are here to bear witness, and as recorders of history we must share our gifts, whenever possible, with those we photograph. It should always be part of any story or project we undertake.